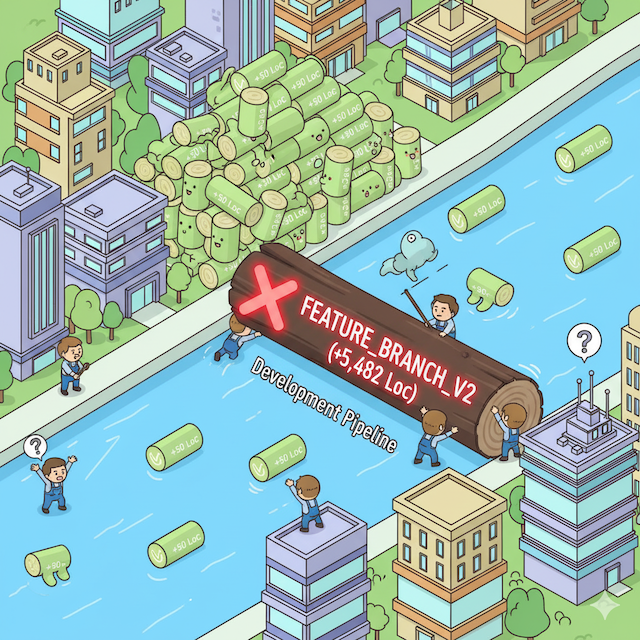

PRs Over 100 LoC Considered Harmful

The Rule I Learned to Love

When Ariel and I started Ariga, he introduced a rule that I honestly thought was going to drive me insane:

no pull requests over 100 lines of code without a very good reason.

I came from teams that practiced long-lived feature branches. You know the drill: you’re working on a feature, you create a branch, and it stays open for the duration of development. Medium to large features? Those branches would live for weeks, sometimes months. I’d regularly see PRs with thousands of lines of code (sometimes even the 10K+ LoC range).

Ariel promised me this was a terrible idea. He’d seen the light at Facebook, where limiting PR size was baked into engineering culture, and he was convinced it was the right way to build software. I trusted him enough to try it, but I’ll be honest: it was difficult to adapt at first.

Five years later, after training our entire engineering team to work this way, I’m a complete convert. Large pull requests are genuinely harmful to software development, and I want to explain why.

The Hidden Costs of Large Pull Requests

For the Reviewer: A Daunting Mountain

Imagine getting assigned a PR with 2,000 lines of code to review. To do it properly, you need to:

- Carve out multiple uninterrupted hours

- Read through dozens of files

- Understand how everything interconnects

- Probably check out the branch locally to actually run and test the changes

It’s mentally exhausting. Most reviewers will look at that notification and think “I’ll do this later” because the task feels so overwhelming.

For the Author: Stuck in Limbo

You’ve just spent weeks building something. You’re excited to ship it. But now you’re stuck waiting for someone to review thousands of lines of code, a task so daunting that nobody’s available to drop everything and spend 2-3 hours on a deep review.

We have two possible bad outcomes here:

- The PR gets reviewed in a rush. Nobody has time for a proper deep review, so it gets a cursory glance and approved just to move things along.

- It takes forever to get started, and processing feedback becomes a slog. When the review finally happens and generates dozens of comments, addressing them all, pushing updates, and waiting for re-review turns into a painfully slow back-and-forth process.

Either way, the real problems start.

The Review Quality Problem

When you’re staring at thousands of lines of code, you face two perverse incentives:

First, there’s a hidden social pressure against deep feedback. If something is fundamentally architecturally wrong, asking someone to throw away weeks or months of work feels like a dick move. You might be right (it might be exactly what the product needs), but emotionally and socially, you’re going to come off as the bad guy. So you pull your punches.

Second, it’s nearly impossible to pay attention to details in such a large chunk of work. There’s a joke in software engineering: give someone 500 lines of code to review, you’ll get 5 comments. Give them 5,000 lines, you’ll still get 5 comments.

When reviewing a massive body of work, you naturally gravitate toward visually obvious issues that jump out at you. You’ll comment on syntax, naming conventions, minor style issues (things that are important, sure, but nowhere near as critical as architecture, design decisions, or performance implications). The tricky stuff, the stuff with fundamental implications for the product, gets a pass because it’s just too mentally taxing to evaluate in context.

The Integration Tax

Here’s another hidden cost: integration becomes an order of magnitude more expensive.

If you’re working in a busy repository (and many of us are), you’re not the only person committing code. That’s literally the point of source control: to facilitate concurrent development by multiple people. (Today, it’s not just humans; it’s AI agents too.)

When you sit on a branch for weeks, you’re working from a version of the codebase that’s rapidly becoming ancient history. Eventually, you need to merge your work back in. You’ll need to rebase or merge all those upstream changes, and conflicts are inevitable.

Sometimes fixing conflicts is trivial. Other times, someone merged something fundamentally incompatible with your approach. Now you’re either reverting their work or completely rearchitecting yours. Either way, the cost of integration skyrockets.

The Rollback Problem

Let’s say you merge your massive PR, deploy it, and discover a critical bug in production. Now what?

Sure, you can technically revert the entire PR. Git will let you do that. But the blast radius is huge because even a well-focused large PR does a lot of things.

Say you shipped a new API endpoint in an 800-line PR. It touches the database layer, adds new authentication logic, updates 15 different files, adds validation, logging, metrics. All for one feature. Then you discover that a seemingly innocent change to the database connection pooling is causing timeouts in a completely different part of the application.

Now you’re stuck. The one problematic change is buried in 800 lines. You can’t just revert that one thing - it’s all tangled up with everything else. So your options are:

- Revert the entire PR, losing all the good work

- Keep the broken code live while you diagnose and patch forward

- Try to cherry-pick the bad commit out (if you can even isolate it)

All of these are painful. And if other engineers have already built on top of your changes, reverting creates conflicts with their in-flight work.

So instead, you almost always end up patching forward: checking out the code, fixing the bug, testing it, pushing it through your CI/CD pipeline. The undo button is technically there, but the cost is so high that it’s rarely practical.

The Alternative: Working in Small Diffs

The idea of working in very small increments isn’t new. It comes from Lean Manufacturing, the system Toyota developed as an alternative to the batch production methods of large American factories.

Here’s the core insight: it’s better to produce cars piece by piece, not in large batches.

This sounds counterintuitive, right? Surely doing the same task repeatedly makes you more efficient through specialization and muscle memory?

The Wedding Invitation Experiment

There’s a simple experiment that demonstrates why small batches work better. The task: prepare 50 wedding invitations to mail out. Each invitation requires:

- Folding a letter into thirds

- Putting it in an envelope

- Sealing the envelope

You can approach this two ways:

Mass production: Fold all 50 letters. Then stuff all 50 envelopes. Then seal all 50 envelopes.

Single piece flow: Take one letter, fold it, stuff it in an envelope, seal it. Repeat 50 times.

Intuitively, most people think batch mode is faster. You’re specializing! You’re getting efficient at each motion through repetition!

But when you actually run this experiment (and there are plenty of videos online demonstrating it), piece-by-piece wins. Every time.

Why?

The Waste of Inventory

When you watch someone work in batch mode, you notice something: they introduce a ton of unnecessary movement. Instead of just holding a piece of paper, folding it, and immediately putting it in an envelope, they’re constantly managing inventory.

After folding each letter, they:

- Set it down on the pile

- Straighten the pile so nothing falls apart

- Later, reach back to the pile to grab a letter

- Handle it again to stuff it into an envelope

Those three or four extra hand movements per letter are pure waste. They don’t contribute anything positive to the outcome. They only exist because you created an intermediate state: a mini warehouse of folded papers that needs to be maintained.

Piece-by-piece work eliminates that inventory. Every motion contributes directly to completing a unit of work.

From Manufacturing to Software: Trunk-Based Development

This same principle translates to software development through a practice called trunk-based development. The core idea: disallow long-lived feature branches, minimize work-in-progress, and limit pull requests to small, reviewable chunks.

Now, the wedding invitation analogy isn’t perfect. Physical assembly and software development aren’t identical. Sometimes a cohesive 300-line refactoring actually reduces cognitive load compared to five scattered 60-line PRs, because all the context is in one place. The analogy breaks down when changes are tightly coupled. But the core principle - that working in small increments reduces waste and accelerates feedback - holds true.

100 lines of code isn’t a magic number; it’s an intuitive heuristic. In fact, we never actually enforce the one-hundred-line limit. If a PR needs to be 150 lines to make sense, that’s fine. But we created a culture where it’s acceptable for a reviewer to say “This is too big, break it up.”

The Objections

“But My Feature Can’t Be Broken Down!”

I hear this constantly. The temptation is to think “this is all interconnected, I need to build all of it together.” But in most cases, what you actually need is to be intentional about the order in which you build.

The key insight: almost any feature can be broken down if you have the right practices in place.

What You Need to Make This Work

A comprehensive and fast test suite. If it takes significant work or time to safely merge a tiny change, small PRs won’t work. You need confidence that your tests will catch issues quickly. Without this, you’re flying blind, and the overhead of validating each small change becomes prohibitive.

Feature flags (or just… don’t call the code yet). This is critical, and it doesn’t require some enterprise feature flag system. The concept is simple: you need a way to deploy code that isn’t ready to be exposed to users.

This can be:

- A boolean constant in your code

- An environment variable

- A config file setting

- Or just… don’t wire it up yet. Merge the function, even if nothing calls it.

If you have a proper feature flag system (LaunchDarkly, etc.), great - use it. But if you don’t, it’s fine. The point is being intentional about decoupling deployment from release. You can build an entire feature incrementally, deploy it to production with the entry points not yet connected, and only expose it when you’re ready.

Building and testing components in isolation. Write the new function. Test it. Merge it. Even if nothing calls it yet. Then, in a separate PR, wire it up. This feels weird at first (you’re merging “dead code”), but it’s actually safer. Each change is small enough to reason about, and you’re progressively assembling the pieces.

The discipline here is planning. You need to think through your implementation strategy upfront. What’s the scaffolding? What’s the first piece of real functionality? How do I add behavior incrementally?

“This Adds Too Much Overhead”

This is the objection I hear most often, and I get it. More PRs means more reviews, more CI runs, more merges. Seems like overhead, right?

Here’s the counterargument: by significantly lowering the cost of review, you actually get reviews much faster. It’s incredibly easy to review a 20-line change. You can read it, understand it, and approve it in minutes. I’ve had PRs that went from “submitted” to “merged” in under 10 minutes. Try getting that turnaround time on a 1,000-line PR.

This creates a virtuous cycle: small PRs get reviewed quickly, which means you get feedback fast, which means you can keep building without getting blocked. Again, this relies on having good and fast tests. If your CI takes 30 minutes to run, yes, this will be painful. But that’s a problem you need to fix anyway. Small PRs just expose it.

Review turnaround still slow? Two things:

-

You need team buy-in. If someone sends a small PR, it should be socially acceptable to expect a quick response because it’s blocking their work. But also - when PRs are simpler - more people can engage in reviewing them! This is part of the cultural shift: small PRs deserve fast reviews. Make it a team norm.

-

You can stack PRs. If you’re waiting on a review, you can branch off your unmerged PR and keep building. When the first one merges, you rebase the second. Yes, it requires some git discipline, and I won’t pretend it’s trivial - managing a chain of dependent branches can get messy. But for many teams, it’s worth learning.

Here’s the real overhead you should worry about: work done and not delivered.

This is the core principle of the Lean movement. Eliminate waste. And the worst kind of waste? Completed work sitting on a shelf. Huge PRs carry the risk of being a complete throwaway because you’re building in the dark without getting feedback.

I’ve seen it happen. An engineer spends three weeks on a feature, submits a massive PR, and during review, someone points out a fundamental issue with the approach. Now you’re either merging suboptimal code because “we’ve already invested so much,” or you’re asking someone to throw away weeks of work. Both options are terrible.

With small PRs, you get feedback continuously. If you’re heading in the wrong direction, someone catches it after 50 lines, not 5,000. The cost of course correction is minimal. That’s not overhead. That’s insurance.

The Prerequisites Aren’t Free

Let me be clear about something: the practices that make small PRs work well require investment.

Fast, comprehensive tests don’t appear overnight. You need to continuously invest in your test infrastructure. This means:

- Writing tests as you write code (not as an afterthought)

- Keeping test execution time down (parallelization, smart test selection)

- Maintaining test reliability (flaky tests kill trust)

CI/CD pipelines need to be fast. If it takes 30 minutes to get feedback, small PRs become painful. You might need to invest in:

- Better hardware

- Smarter caching strategies

- Parallelized builds

- Incremental compilation

Team discipline takes time to develop. New engineers will struggle at first. Code review needs to become a priority, not something you do when you have spare time.

These aren’t small asks. But here’s the thing: these are investments you should be making anyway. Fast tests make development faster regardless of PR size. Reliable CI/CD reduces deployment anxiety. Strong code review culture catches bugs earlier.

Small PRs don’t create these requirements - they just make the absence of these practices more painful and obvious. And that’s actually a good thing, because it forces you to fix foundational issues you should have fixed already.

When Larger PRs Make Sense

I’ve spent this entire post advocating for small PRs, but let me acknowledge: there are times when larger PRs are the right choice.

Large-scale automated refactoring. If you’re renaming a core concept across an entire codebase, breaking that into small PRs might actually make things worse. The intermediate states could be confusing or inconsistent. A 500-line PR that performs one logical, atomic rename is often clearer than five 100-line PRs.

Tightly coupled changes. Some changes genuinely need to happen together. A database schema migration with corresponding ORM changes and API updates might be hard to split cleanly. You could do it (schema first, then code), but sometimes the cognitive overhead of understanding the split outweighs the benefit.

Dependency upgrades that touch many files. Updating a major framework version might require changes across dozens of files. While you could theoretically break this down, the intermediate states might not even compile. Sometimes it’s better to take the hit on review difficulty.

Your team doesn’t have the prerequisites yet. If you don’t have fast tests, if your CI is slow, if your team isn’t bought into quick reviews - forcing small PRs will just create frustration. Fix the foundation first, then adopt the practice.

The key is being intentional. If you’re sending a 500-line PR, you should have a good reason. “I didn’t think about how to break it down” isn’t a good reason. “This is an atomic database migration that touches 47 models” might be.

The Transformation

Looking back on five years of working this way, I can’t imagine going back to long-lived feature branches. The 100-line limit felt like a constraint at first, but it became a forcing function for better practices: better planning, better architecture, better collaboration.

I asked Jannik, a founding engineer at Ariga, how he felt about the practice after years of working this way. His response: “I wouldn’t miss it again. If I ever work for another company, I will try to get this piece as part of the dev cycle.”

What resonated most with his experience:

For him as an engineer, small diffs fundamentally changed how he approached testing. When you structure code in small portions, testing becomes less of a burden. You write more unit tests, and they’re better tests. Code reviews become less interrupting because the context is small - you’re not derailing someone’s day with a 1,000-line review. And interestingly, refactoring happens less often because the continuous feedback loop feels almost like pair programming. You catch design issues early, before they calcify into problems.

For the company, the benefits compound. Code lands in production faster. The smaller context means a bigger pool of people can review any given PR - you’re not limited to the one person who understands the entire feature. More people get involved in every piece of code. Most importantly, you shift left on when you get feedback. Instead of discovering architectural problems after three weeks of work, you discover them after three hours. Dev velocity actually increases, even though it feels like you’re adding process.

Your mileage will vary. Maybe 150 lines works better for your team, maybe 75. Maybe you need to make exceptions for certain types of changes. The specific threshold isn’t the point.

What matters is making small, reviewable, shippable increments your default mode of working. Not a rigid law, but a strong default with intentional exceptions.

It makes code review less daunting, integration less risky, and deployments less stressful. It makes your team faster, your architecture cleaner, and your engineers happier.

Most importantly, it makes you ship. Continuously. Without the anxiety of big bang releases.

That’s worth the adjustment period.